This is a crucial distinction that is frequently confused. Basically, specification limits have to do with the voice of the customer while control limits have to do with the voice of the process.

First off, what are the specifications? Specifications define the allowable deviation from target or nominal. But to really understand what is going on, we have to define what we mean by “allowable deviation,” “target,” and “nominal.”

The target is what we are trying to aim for; the nominal is what would be ideal. Target and nominal are frequently, but not always, the same. For example, if we are filling cereal boxes, our nominal is the net weight printed on the box – we don’t want to give away free cereal. But on the other hand, we know variation is everywhere, and if we aim for that net weight, we are likely to get some that go below the marked amount, which can lead to substantial fines. In that case our process target is higher than nominal so that we don’t have any boxes below the net weight.

How is the nominal determined? Strictly speaking, the true nominal is the point at which the process losses to both you and your customer (and end-users) are at a minimum. In my experience, however, the difficulty of performing this calculation means it usually is not done and the supplier ends up determining the nominal based on internal losses or using an industry standard nominal.

The allowable variation around the nominal is also ideally based on losses. The specification limits should be placed at the point(s) where the losses due to the variation (at the supplier, customer, and end-user) are equal to the benefit of the product.

Again in practice, this is sometimes difficult to quantify. Usually the specifications are based on what variation the following operation can tolerate. Sadly, since the total losses are not considered, specification limits are frequently too tight or too loose and cost society uncountable billions of dollars.

Control limits are based on past performance. They are the voice of the process telling you what variability the process has produced in the past, with the intention of recognizing when a sufficient change from the past has occurred to justify adjusting the process.

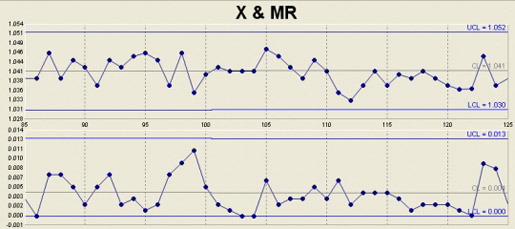

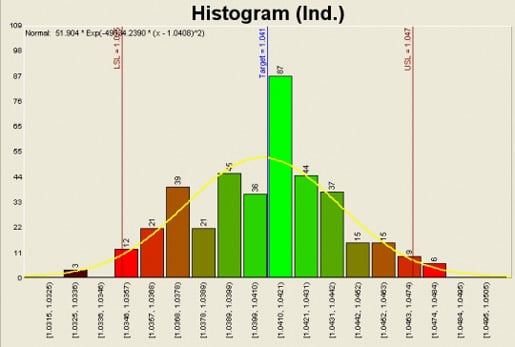

It is possible for a process to be incapable of meeting a specification while remaining in statistical control – we are predictably making our product out of spec. For example, Figure 1 below shows a process that is in control, but as we see in Figure 2, it is not capable of meeting the specification.

Figure 2 – Histogram of Process Output with Spec Limits

Further, as Dr. W.E. Deming showed us, adjusting a process that is in control results in increased variability. If a process is in control but not capable, then adjusting the process when it goes out of spec will actually increase the variability over time, making it even harder to meet the specification.

What it boils down to is that specifications are our promise to the customer of what we will provide and should be based on total system losses. Control limits show the range of variability we expect from the process and are based on actual process output. While process variability affects the total process losses, the specification limits in no way influence the control limits.

Recent Comments